Let's specify the derivation tree more precisely, so we can compare this to what happens in the software domain precisely.

An expression derivation tree is a standard tree structure. A tree structure connects nodes. Each node can have any number of children. A node can be a child of only one node. Each node has certain properties. The parent-child relationship (represented in a figure with a line connecting them) may also carry certain properties in the connection. For more complete information about tree structures, consult the web (or Wikipedia).

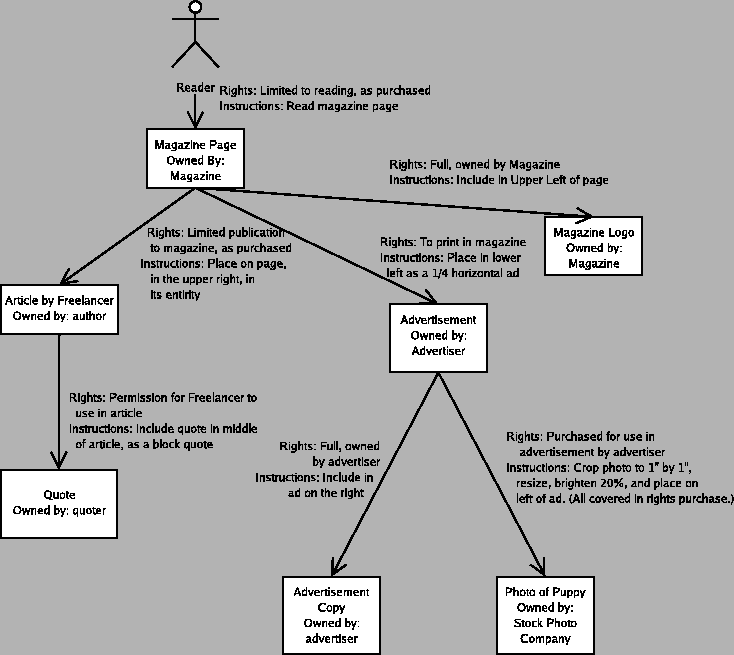

Trees are immensely useful structures, and are used in many different ways. In my derivation trees, all nodes represent some expression, perhaps some text, or a picture, or a movie. Each of these nodes has at least the following properties:

- Some collection of rights distributed to the owners of that expression. Every expression is owned by some set of entities. It can be owned by one entity, several entities (in the case of a collaborative work, for instance), or no entities, in which case we call it public domain. Each entity may have varying rights to the expression. For instance, there may be a primary author who is authorized to distribute some work, while the other collaboration partners may only have full control over their own contributions. If there is no owner, then nobody has any ownership of the expression, and it can be used freely.

- The expression itself that the node represents.

- Links to any children it may have. In the static world, expressions always carry their children with them. (For example, the "magazine page" has as a child the advertisement; every copy of the magazine page has a copy of the advertisement as well.) If this is a composite expression as described in the owner-rights paragraph above, then that work also has as children all the separate pieces. Each of those children would also contain a full set of properties describing who owns it. These are shown in the figure by the arrows.

Note that these are integral parts of the expression; if you throw the children away, it is not the same expression. That would represent an expression independently derived, with no children. For instance, in the magazine page instance, if you threw away the advertisement child but the final product remained the same, that would mean that author of the magazine page actually created the advertisement themselves. That's not the same thing at all, because that would imply the author of the magazine page would then have full rights over the advertisement, which they do not. Current copyright law does indeed treat fully independently derived expressions that are the same as separate expressions, in the rare cases where it happens.

Along the links from children to parents multiple things flow:

- The rights to use that expression. Many different kind of rights flow, everything from full rights to just the right to use it that one way. This is determined by the agreement between the copyright holder and the entity using the expression.

This is important to keep track of, because for a given parent expression, different children may communicate different rights. For instance, for a magazine, they might have the rights to publish an advertisement in the magazine issue, but they might not have the rights to put that whole page online on the web, because the advertiser may not grant "online rights" to the advertisement. They could still put their articles on the web, though, because the magazine owns full rights to their own works.

- The instructions on how to derive the parent from the children. This is a subtle point that would be easily missed if we were not eventually going to contrast this with software. For instance, a stock photo used in an advertisement is not generally just placed in the advertisement. It might be rotated 30 degrees clockwise, shrunk by a factor of 2, brightened 20%, and have the text "It's Great!" overlayed in Verdana 24pt font starting on the upper left corner.

This is also an important part of the expression because different legal effects can occur, based on how the work is used. The most important example of this is when the instructions describe a use consistent with fair use. That may mean that the parent has rights to use the expression in the way described with the instructions without permissions from the original copyright holder, but used differently (larger quote, longer snippet, etc.), normal copyright may apply. If we don't carry along the re-creation instructions, then we don't have the full picture of what's going on legally.

It is easy to see with all of this how one can make a living just tracking and enforcing the relationships that arise in the copyright domain. The larger the composite work, the more sources for a work, the more complicated the story becomes.

|

Note that even as verbose as this image is, and as oversimplified as the example is, even this isn't complete. For instance, does everyone have permission for the fonts used? How often do you think of that? In the real world, everything except maybe the stock photo and the quote would themselves break down into further composite expressions, but this should be enough to give you the idea.

Take a look at the Instructions for the Advertisement: Just because the advertisers bought space in the magazine to print their advertisement does not mean that the magazine can do whatever they like with the advertisement; they are obligated to do neither more nor less then what they agreed with the Advertiser. Also note that there are two instances where the owner of a composite expression, the Magazine Page and the Advertisement, where they also own one of the components. It's important to still show the sub-expressions, so one does not get the impression that the advertisement consists solely of a stock photo, which would be unlikely to be a compelling advertisement unless you got really lucky with someone's stock photo.

It is a common misconception that once you create an expression, you own full rights to that expression no matter what. In reality, what you own is certain rights to control how your work is used in other works. It is possible that someone else will completely independently come up with an effectively identical expression, and they will own full rights to it as well. It is recognized by the court system that fully independently coming up with the same expression is a very remote possibility, but it has happened before, especially in domains such as "musical melodies" where there are not necessarily a whole lot of distinct melodies to be copyrighted.

The derivation tree is just an equivalent way to represent the expression, one that highlights the complicated legal status of the expression; it is neither more nor less true, it's another view of the same thing.